Jessica Meir | American NASA Astronaut, Marine biologist, and Physiologist

When rejection is re-direction | On following your dreams

Jessica Ulrika Meir is an American NASA astronaut, marine biologist, and physiologist. She was previously an assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, following postdoctoral research in comparative physiology at the University of British Columbia. She has studied the diving physiology and behavior of emperor penguinsin Antarctica, and the physiology of bar-headed geese, which are able to migrate over the Himalayas. In September 2002, Meir served as an aquanaut on the NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations crew. In 2013, she was selected by NASA to Astronaut Group 21. In 2016, Meir participated in ESA CAVES, a training course in which international astronauts train in a space-analogue cave environment. Meir launched on September 25, 2019, to the ISS onboard Soyuz MS-15, where she served as a flight Engineer during Expedition 61 and 62. On October 18, 2019, Meir and Christina Koch were the first women to participate in an all-female spacewalk.

Can you take us back to when you started your masters education. What led you into this specific field?

Before I went to graduate school I was actually working here at NASA. I graduated from my undergraduate and went to the masters program at the international space university in France. A part of the program was actually a work internship period. Though that, I got a position working as a scientist at NASA’s space centre, where I am now.

I actually did work here at NASA in Houston for 3 years many years before becoming an astronaut. I lived here for 3 years then I ended up going to graduate school. I had this career here, and everything was going well. I had some really interesting opportunities and some unique ones like flying in the C 131, the vomit comet, the airplane that flies in parabolas in weightlessness, and living underwater in an underwater mission and things like that. At the time I had always imagined that I would go back to school, either a PhD or an MD.

I was also really into medicine, going back and forth between what I wanted to do, and came across this really interesting work that was being done at the institution of oceanography, which is part of UC San Diego with Jerry ___ and Paul ___ and this really cool work they were doing looking at diving physiology of extreme animals. I had an interest in diving and I had done an underwater mission at NASA and had my scuba diving certification. I saw this work that these scientists were doing and it blended all of these things that really captured my interest, imagination.

They were doing work in the Antarctic, with really cool species, like emperor penguins and different sorts of seals in California and they were looking at the diving physiology trying to understand how these animals can exhibit such incredible diving behaviour. Animals like an elephant seal can dive for two hours on a single breath. An emperor penguin can dive for half an hour. These are air breathing divers just like you and I would be, but they have a far superior capability at diving. We are trying to understand what is it about their underlying physiology that really explains that.

I was interested with the type of work they were doing and the fact that it blended these really interesting scientific questions with working in an extreme environment like the antarctic and doing really physiology, and like I said, I had this interest in medicine as well. It was real physiological work that they were doing. Paul P__ who ended up being my PhD advisor, he’s an MD PhD, so he actually works as an anesthesiologist full time. That gives him the expertise to do this kind of research on animals in a way that other scientists really couldn’t.

The general theme that I refer to a lot in terms of my interests and passion all throughout my life, this theme of exploration and being curious and this inquisitive nature of trying to understand more about the world around me. That was something that was really instilled in me since I was a kid, just exploring the woods and nature. You can kind of see how this is naturally inclined with why I wanted to see that work for graduate school. It was random with internet searches. I ended up going to trips, working with Jerry and Paul, doing this work in the antarctic with them and penguins with elephant seals in California.

At the time, it’s really interesting because I always had this dream of potentially becoming an astronaut, since I was 5 and I had worked at NASA, like I had mentioned, but I left NASA because I knew that I wanted to do my own science and I thought “I probably won’t ever go back to NASA unless it was to become an astronaut, but that will never happen because it’s such a small chance.” I felt incredibly fortunate to have found this other career that I found really fulfilling because it combined all of these things, science, working in an extreme environment, being outside in nature with these animals in their natural habitat, and so that to me was so incredibly fulfilling and doing that work in the Antarctic, that was the first time that I had really felt completely content. I had this mental and physical challenge doing this kind of work. I felt so fortunate because I thought “The chances are so slim, I’m sure I will never become an astronaut.” I was always secretly worried that that would mean “am I ever going to actually be happy?” I felt so lucky that I had found this other career that felt equally as fulfilling and that kind of ends up becoming the ironic part about it. All of us who become astronauts, we do so because we made our way and forced our paths in some other field, and then we have to leave that field in order to do this job.

What was the transition that took you from that career path into becoming an astronaut.

I always tried to pursue both, ever since I was little. I always wanted to be an astronaut but biology was my favourite subject. I had always, even though I was doing biology, which some people think might not be directly applicable to being an astronaut, I was still involving myself in any sort of space related activity or NASA program. There were several from going to space camp at Purdue university when I was in high school, or doing a summer program when I was in college at the Kennedy space centre. I always had one foot in that. As I mentioned, since I worked here as well, I knew astronauts, I worked with them. When I was working here I was working with the human life science experiments that the astronauts are subjects for. I was training astronauts and working for them.

I had built connections. It was just a matter of applying. With NASA, becoming an astronaut, like all federal positions, it starts on USA jobs website where you’re filling out a resume, and there are a few additional forms and then of course NASA undergoes this whole selection period. I really started applying to be an astronaut as soon as I was realistically competitive, and I had even interviewed before this class. When I was in graduate school, I was just finishing grad school when they picked from the class before my class. I did an interview for that one and made it all the way to the final round, and I wasn’t selected for that one. It was kind of like, this is what I expected. I made it pretty far. It was nice to be back at NASA and to see everybody and to know that I had made it to the final round, but the numbers are so small. I had kind of accepted it at that point that it was never going to happen. 4 years later, there was another selection and I applied for that one and that ended up differently.

The advice I always try to give is that you have to be willing to take a risk and be willing to do something slightly outside of your comfort zone. I think that’s really critical to making these sort of big leaps and making your dreams come true, but it’s scary. It can be really daunting. I always try to encourage people to just try to remember to be willing, to not be afraid to take that risk, and also to realize that failure is part of the process. You shouldn’t be afraid to fail, that’s when you learn the most important lessons. That was true for me too. I failed. I wasn’t accepted that first time. It would have actually been very easy for me to say “Okay that’s it. I don’t want to apply again.” To be honest, I actually did sort of talk about that. When the chance came to apply again, I knew what it was like to go through that process, and there was a lot of stress. There’s a huge psychological component going through that entire process. I thought “I don’t know if I want to put myself through that again.” Of course, I realized that I had to at least try. There was a lot of back and forth in my head thinking “Well I have this other career. I’m so lucky to have found this other career that I really like and that I’m doing well at. Maybe I don’t need to be an astronaut. Maybe that’s not the right thing for me anyway. Maybe I just won’t apply.” But, you have to keep trying.

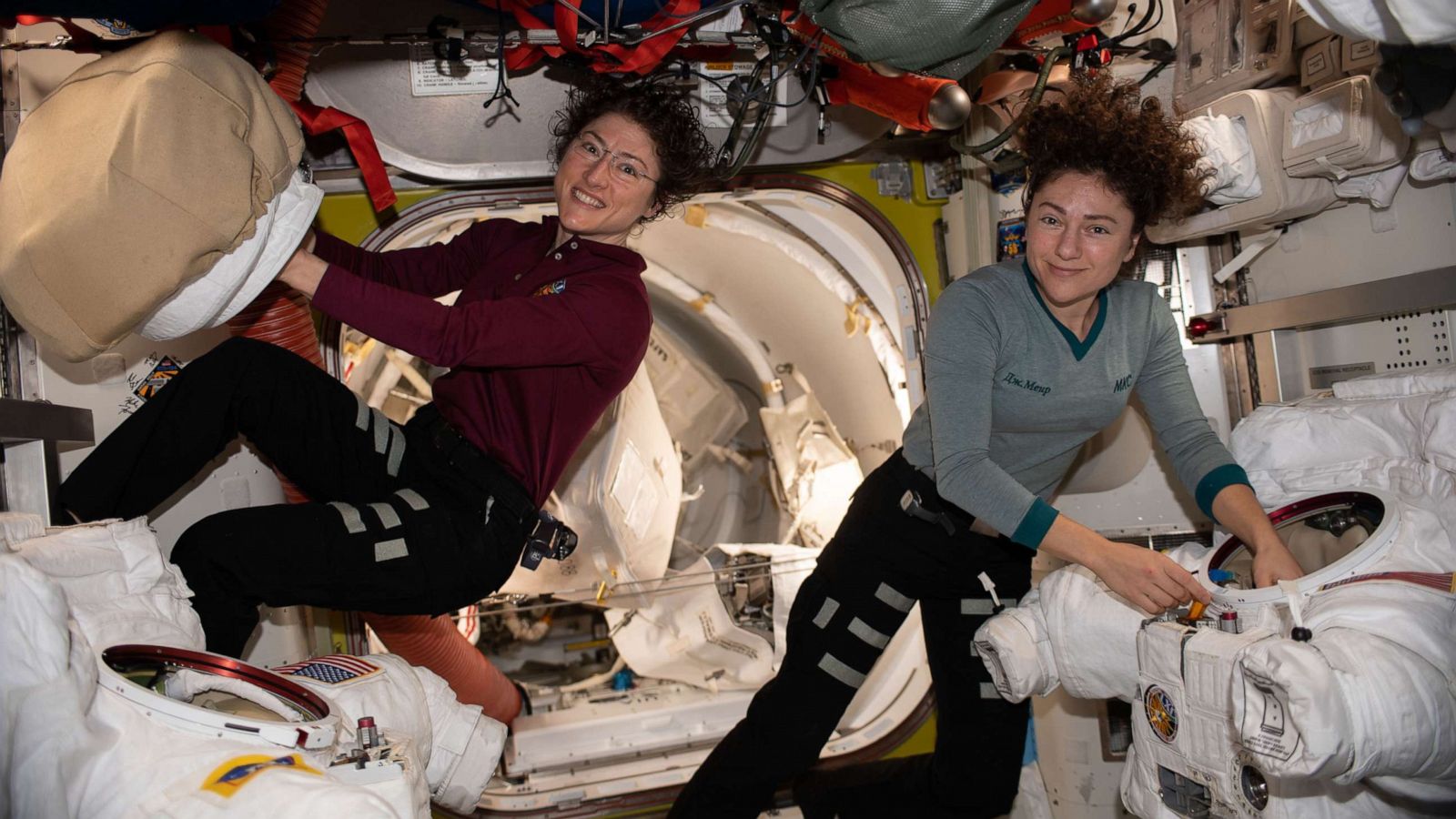

By doing so you also became the first of two women alongside Christina Koch to have done a spacewalk. Can you tell us about that experience?

That was, for me, this dream I always had about being an astronaut and going to space, the one thing that I really wanted to do on my mission was to do a space walk. There is no guarantee that you’re actually going to do a space walk during your particular space mission because we just do them when they’re required. There was no guarantee, but I was really hoping that I would get to do one. It just kind of happened to be the way the stars aligned when Christina and I were both up there at the same time. It’s sort of an interesting process, that whole discussion for me. Christina and I were in the same class in 2013.

When we became astronauts, we were the first class that was 50% female and 50% male. We got a lot of attention because of that. Sometimes we were thinking, why are we always talking about this? Why are we bringing so much attention to this? Shouldn’t it be normal? We’re just an integrated group now. I thought about it quite a bit differently back then. It was kind of the same thing at the beginning of the space walk. Christina and I were both on the space station. We all had the same training, been held to the same training standard. Everybody on the space station was qualified to do a space walk. It could have been a mix of any, at the time there were 2 women and 2 men at the US segment. It just so happened that the odds are now, we did a lot of space walks during our mission, and if you’re rotating through you’re going to end up having 2 women do the space walk. Of course, that had never happened before. There had been other women who had done it, Christina was the 14th and I was the 15th woman to do the space walk, but never two at the same time.

It’s the same kind of thing when we are up there. At first, I was thinking “well, why is this such a big deal, can’t we just be celebrated for our achievements. Why does it have to be because we are women?” We also sort of looked at it as “We’re just going to do our jobs today.” That’s the important part. Space walks are actually the riskiest thing to do and the most challenging to do, both physically and mentally. It really does demand 100% of your concentration, especially for your very first space walk, where you’ve never done it before. You’ve done all of this training but you have never been in the vacuum of space in a space suit. I was 100% focused on the task. There was starting to be a lot of talk on the ground of the first all female space walk and I was just like “I need to ignore this,” because I need to make sure I know how to do my job, and accomplish the mission. I tried not to think about it before the space walk, but afterwards, I think it really did transform how I thought about it because, first of all, I was quite shocked with how excited everyone was on the ground. How much enthusiasm and support. There was this outpouring of people, just engaged in it. Most of the time, people aren’t watching space walks.

They’re pretty boring to watch. I was really surprised by how many people were paying attention. I started thinking about it, and I thought it doesn’t really matter how I feel about it. I feel how I should because we are at the point where we have two women doing a space walk, but the only reason we are, is not because of my personal achievements, its because of these decades and generations of women and other minorities that really were pushing the boundaries and breaking the glass ceiling when we didn’t have a seat at the table. Obviously, we still have much more room to approve in the US and around the world, but we’ve come a long way and I started realizing that this is the moment to celebrate them. If it happens to be Christina and me up here the can do that, that can help inspire, we need to do that as our responsibility for all of the work that they did at getting us here. I started thinking about it that way. People were paying so much attention to it being Christina and me that did it, and I thought, well, it’s not really about our personal achievements, its about these other women, so let’s celebrate these other women that got us here. That made me think about it a lot differently and realize how important it was, and then the part that Christina and I that was us paying homage to these generations, but now serving as an inspiration to others, to young girls and really anyone that has a struggle and has a dream. It doesn’t have to be our dream, but whatever that dream is, to realize that they can achieve that. It really did take on another meaning to me, that whole evolutionary purpose.

About paving the way, did you have inspirations when you were younger? You wanted to be an astronaut since you were 5, were there women astronauts or astronauts in general that you were inspired by?

It kind of was. At the time when I was growing up, in the 80s and 90s, the space shuttle program was extremely active. I grew up in a small town in northern Maine, my parents were both from other countries, we didn’t know anybody that worked at NASA or anything. It was different growing up then because there was no internet. You get your news from the newspaper or the evening news, and all of the space shuttle launches were always on the evening news, and I saw that then. Of course there were female astronauts launching on some of those missions, but to me it seemed normal that there were all kinds of people involved. Maybe because I grew up with three sisters and 1 brother, I was surrounded by really smart inspiring women. I was the youngest of all of them. Of course I realize, I didn’t realize it back then, but looking back on it, I was extremely fortunate that I didn’t ever feel that I couldn’t do something because I was a girl. I never felt that way. I realize that’s rare. Because of that I think that was part of my mentality of doing things. I really didn’t think about things in that way. Role model wise, I think my sisters and my mother were the most powerful female role models I had. My sisters were really diverse and did everything, so I wanted to do everything ranging from academics to arts and to sports and to music. I wanted to do it all because they were doing it all. Those were some of my strong role models. Of course, watching the female astronauts and other scientists as well, that’s kind of normal to me.

What is the advice you would have given yourself when you first started? Your studies or in your dream position?

If I look back on it, I tend to, like a lot of people, really forget to enjoy and appreciate the moment. I think that you’re always looking at what’s next and trying to achieve the next thing. There’s always the next thing. If you’re always living your life that way, you’re kind of missing out on the most important part. I had such incredible experiences all throughout my life, from the time I was a kid and through college and beyond. I wish that I could have realized then to maybe take a little bit of pressure off of myself. The importance to stay motivated and to drive yourself, but I think sometimes that gave me a little bit too much stress. It was usually self-imposed stress. It didn’t come from other people. I think I would look back and tell myself that I would take a deep breath and enjoy the process and the journey and what’s going on, and to realize that maybe I don’t need to put that much pressure on myself, and it’ll still work out. I don’t know, maybe if I hadn’t done that it wouldn’t have worked out.

What motivates you at this point and time?

I think it’s really still that basic curiosity and that desire to explore and look around the corner. I think that’s really just an innate characteristic of humans. We didn’t have that desire to look around the corner and go further, we never would have even finished exploring this planet, let alone going to the depths of the ocean now and leaving this planning. I’ve always been drawn to that, and that’s always been something that has inspired me and that has led to my previous career and this career, just understanding more. For me now, after having achieved my goal and being in space, there’s some personal objectives as well that I would like to try to look at a little bit. In terms of professional objectives, we’re involved with the arguments? Program, and we are taking the steps to go back to the moon and to go on to Mars. We are building the Orion vehicle and the space lawn system. I think to me, my dream mission would be one of those people going to the surface of the moon. Whether or not that would happen, I’m certain to be involved in some way, so it’s really exciting time for us as astronauts because there are all these different missions going on. We’re still flying the International Space Station, we have new vehicles being developed here in the united states. We’re launching with space X from Florida again. Boeing is building us a new vehicle as well. We have the Orion space capsule in order to go further, to go to Mars.

I also think it’s really encouraging to see the dispersion in the commercial sector, where if you’ve seen what Space X Is doing, there’ll be tourists that would be flying in their capsule later this year and next year. There are so many different types of companies and entities that are doing things from the space sector, even if it’s not going all the way to the space station, doing a sub orbital flight like Virgin. There are so many other companies that are getting more people involved in space life. To me, that is just so exciting and encouraging the space is becoming more accessible to more people.

Would you ever write a book in the future?

Jessica: a lot of astronauts write books. It’s kind of a thing. Most of them do it after they leave NASA. As federal employees leave, we can’t really engage in other careers or anything that has any monetary gain, so a lot of people wait until after. Yeah, it’s something I’ve thought of. It’s funny, that’s something I thought about since the time I was a scientists, and one of the thing Is really wanted to do was to write a children’s book about some of the work that I did. For my post doctoral research and position, I raised 12 goslings and trained them to fly in a wind tunnel to study the physiology. Either high altitude birds that fly over the Himalayas. Kind of like a diving animal, they’re not holding their breath, but they’re flying at an altitude that there is such little Oxygen. We were trying to understand how they did that. I really wanted to write a children’s book about that. It is still something I want to do. I haven’t thought exactly about what I might want to write, but it’s definitely something I would think about.

Another one of the things I like to talk about is the element of teamwork, and how important that is for success, for women or for anybody, and recognizing that aspect of being a team player and how it’s really when we’re truly successful it’s not a bunch of individuals, it’s the team that gets us there. That is so embodied here at NASA. We as astronauts are the figures that do the interviews and the faces that people see, but we are just a tiny fraction of the hundred and thousands of people here at NASA that enable us to complete our missions. They’re the ones that are the true experts developing all of the hardware, analyzing everything, monitoring our safety while we are in space. That’s something that people need to remember, that it really is our team effort that truly makes us successful, and how important diversity in those teams are. I’m sure you’ve seen those studies about how more successful those teams are that have more diversity. Not only are they more successful, but people have more job satisfaction. You have different ways of working and solving a problem, it just makes it so much more interesting. You are so much more able to be successful and accomplishing any mission when you have different ways of solving a problem. We see that with NASA now with our diverse crews ranging from military test pilots to scientists like me, and people of all shapes and sizes and colours. I think that just makes it a much more interesting experience.

Talking about that too, I see you were also a private pilot, right? You have your PPL license?

Yeah. We actually do all flies at NASA 38 the jet, once we become astronauts. There isn’t actually a requirement to be a private pilot, but flying was always something that interests me so I started doing flying lessons when I was in undergrad.

All photos provided by NASA

Get your hands on the latest tips and tricks of what it means to be a #GOSS. In this free e-book you will dive into 11 business traits that will help you grow your business!

11 Ways To #BeGossy E-book

FREE DOWNLOAD

Find out more inspiring stories from women worldwide of all industries. Follow us on Instagram @GossMagazine.

website design Credit

© Goss Club Inc. 2024 | all rights reserved |

Inspiring & empowering women worldwide.

© GOSS CLUB INC. 2024 | all rights reserved

Share to: